New England native Micky Metts has made her mark as a behind-the-scenes, coalition-building, ego-free artist. She’s self-taught, a true buccaneer scholar with sentinel intelligence – traits that make her highly intuitive, obsessive about her passions, and wary of the inconspicuous perils of society.

In some cases, her altruism and anonymity underscore the integrity of her work. In others, Boston historians have simply overlooked the presence of her mid-’70s punk band, the Phantoms.

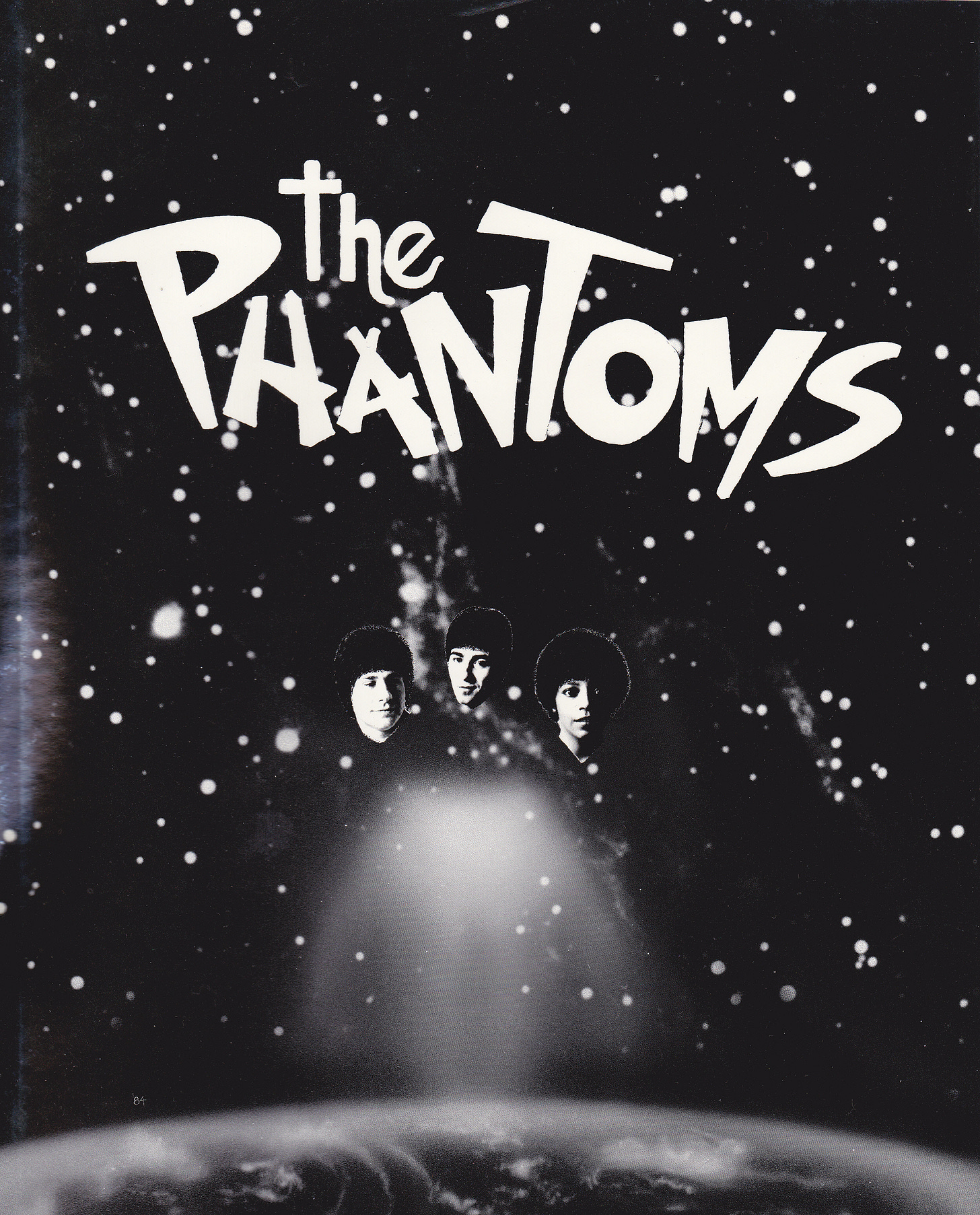

Image courtesy of Donald Garner.

“[The] Phantoms were in a subset of Boston's rock scene where the emphasis was on camaraderie as opposed to aspiring to a power position,” Micky said. “We rarely got a sound-check [while] other bands seemed more focused on who was more popular on stage, with the club owner, and at the bar. This is sad because many bands did not get paid, they got a bar tab.”

She describes early punk in Boston as consisting of three scenes: bands aspiring to fame, bands traveling from the suburbs to gig in the city, and independent bands who often performed at underground venues.

The Phantoms hosted lesser-known bands at their basement spot, Club One. This is where she first encountered the cooperative ideals in the punk scene. “We had a group of bands that were invested in unknown musicians getting a fair shake at playing for an audience. When a new band formed, we would often share equipment and ask each other to play at shows,” she said. “There were cool bands with women like ZodioDoze, The Earotics, Fine China, The Hendersons, Modern Electrics, Little Green Men.”

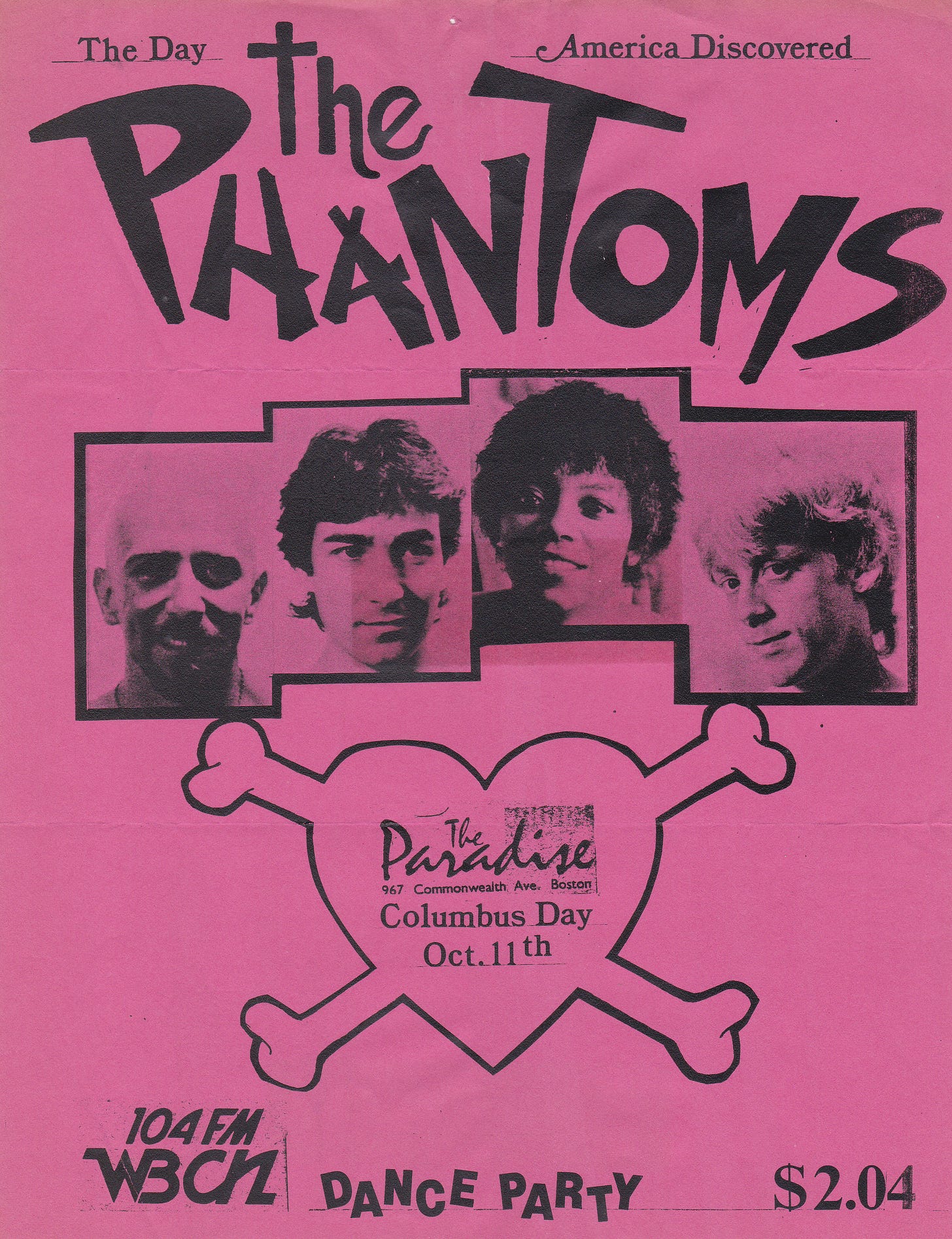

The Phantoms playing at Club One. Image courtesy of Donald Garner.

She also suggests that the band may have gotten overlooked because the Phantoms weren’t interested in partying the same way as many other bands were. She said, “We were not a drinking band and did not hang out at local bars. There was a clique of bands that drank together.”

When playing at bars, the Phantoms won over crowds, and in local media, they got attention. Nevertheless, some musicians and audience members outside their scene treated her with outrageous disrespect.

“One night after a show, a young man challenged me in the parking lot when we were packing up,” Micky said. “He was screaming and yelling that I wasn't playing the guitar and a man was standing behind my speaker off-stage playing because women can't play guitar like that.”

“At one gig, the guitar player from the headlining band walked by us, kicked my guitar case, and told me to scram,” she said.

Though her band’s legacy remains hidden, there are no secrets about her. She dedicates her life to transparency and liberation, which is most apparent in her work advocating for free software.

“Free software is licensed under a GPLV3 which means it all must remain free for public use, Micky said. “We will have no freedom without free software. Corporations already have the upper hand.”

“Apple markets themselves on privacy but they are being disingenuous and confusing in their marketing language,” she said. “People aren’t knowledgable enough and don’t look into it.”

I’ve connected with Micky over encrypted messaging via Signal and CommunityBridge video chats for the last few years. I contacted her because a friend linked me to her band The Phantoms on YouTube (in which Micky sings and plays guitar), and I wanted to interview her for my book, Hit Girls: Women of Punk, 1975-1983.

Despite her openness, generosity, responsiveness, and resilience, she remains an enigma. After talking to Micky, I learned that over the last few decades, she has seemingly lived a thousand lifetimes. In one, she radically modified late 1960s Volkswagen Beetles; in others, she worked as a silversmith, welder, and even a formula racing pit crew member.

“I am a metalhead and used to be a metalsmith,” Micky said. “One interviewer wrote about me as working with light metal during the day and heavy metal during the night.”

Today, she is an activist hacker as well as a member of Agaric – a worker-owned cooperative of web developers – who advocates for internet privacy and freedom through the promotion of free software. She is deeply involved in and committed to various movements and networks in the world of free software, cooperative business models, and community building. She uses and advocates for tools like the conferencing system BigBlueButton, content management software Drupal, and the GNU/Linux operating system and works with the Boston-based Free Software Foundation. She also founded CommunityBridge, which, according to its website, is a gathering place for cooperative-minded people.

To my surprise, the Micky I was looking for — the one who fronted one of Boston’s first mostly unheard punk bands — was not the only version of Micky who existed. But a throughline between her past and present selves still exists, as Micky’s history in the Boston music scene led her to where she is now.

“I remember the day [in 1975 that] I cried and realized how rich people were selling our ideas when I walked into either Bloomingdale's or Macy's and saw them selling fashions that we were wearing on the streets as hippies,” Micky said. “Fringe-sleeved jackets and ripped jeans and things like that.”

Micky turned to punk immediately when she heard the Sex Pistols. “They had an urgency about government abuses in their lyrics,” she said. ”Rock had become corporate with bands like the Rolling Stones completely selling out and encouraging drinking and violence towards each other not at the establishment.”

Leaving the rock world for punk opened many doors for her creatively and politically. “The spirit of punk camaraderie brought me to my current work with the cooperative movement, Micky said, “and drove me to build a YouTube-like site for videos, [which also led] to helping change laws around facial recognition software.”

After nearly two decades, her trajectory into the world of free software and internet privacy first began when she was one of the first to use a video-sharing platform called VDO.net. In 1995, she purchased the URL punktv.com and originally uploaded videos because she wanted to get her bands seen by record labels.

Micky Metts with her Phantoms bandmates. L - Carl Biancucci (bass) and R - Angelo Aversa (drums). Photo courtesy of Donald Garner.

The Phantoms formed in 1976 and, as many bands do, went through many member changes and toyed with a few names – Carnelian, Little Frankie and the Boulevards – before landing on the name that defines their legacy: The Phantoms. When the band was Carnelian, Micky played bass. When that band took on a new name and form, she switched to guitar. The Phantoms played for a decade, but little material proof remains of their existence in punk history. Their flyers aren’t included in punk books. Lists of once-active bands skip over their name. Most of their recordings, if not all, are basement tapes.

“We didn’t do much studio stuff,” Micky said, “we had no money.”

On the band’s website, they say, “We wrote so many original songs over 10 years that we never really had much time to catalog and preserve the tapes, or maybe we just piled them in a box because we were PuNkS, who knows.”

The Phantoms (L-R): Angelo Aversa, Micky Metts, Dash Airheart, and Carolyn Casey. Photo courtesy of Donald Garner.

The Phantoms are no historical hallucination, though. The internet preserves some of their story– the most information coming from the band’s archived website, which houses MP3s and a review by Lorry Doll of their archival CD release “Wagon Loopy” in Neon, Lorry’s quarterly New York City magazine. Google search results lead to some information, including a YouTube stream of their 1982 7-inch “Any Day / Alien,” and a mention from Boston Groupie News.

A few weeks after I contacted Micky, her friend Donald Garner (aka Skreeg) mailed me a flash drive full of band photos and flyers. He also included a copy of “Wagon Loopy” on CD. Without a CD player or disc drive on my laptop, the only way I could play it was on my television through my DVD player.

(You can buy Wagon Loopy on CD here on Micky’s website,punktv.com.)

However, in many histories of Boston punk, it’s as if they were literal phantoms– a figment of the imagination. An extensive list of Boston bands from the Arthur Freedman collection at the Harvard Film Archive doesn’t include the Phantoms but mentions two later male-led metal bands that spawned from the group that Micky played in: The Organ Donors and Diabolix. The Phantoms were among the earliest Boston punk bands to include female members, but even the “Women Who Rocked Boston” documentary forgets them.

Micky says, “A lot of my fans and friends wrote to [the director], so maybe he updated it... I’m not sure.”

Flyer courtesy of Donald Garner.

Lots of bands get swept under the rug. Regardless of talent, so much of a band’s notoriety comes down to being at the right place at the right time, knowing the right people, and having the good fortune to get it documented. But it’s hard not to recognize a pattern when it comes to identity. Even through the ‘90s, bands with women were being told there wasn’t “a market” for women rockers or all-women bands. Additionally, like Tina Bell, Micky is a Black woman who was fronting a punk band in a scene dominated by white men in the ‘70s and early ‘80s. (As corroborated by photos, the two women even sported similar white leather jackets.)

Micky emphasized, “As you may know Boston has deep racist roots.”

Because – until they are co-opted – subcultures start out rejecting the status quo and emphasizing individuality, punk’s historical erasure of Black women calls its very nature into question. That the existence of an artist can only be substantiated when there is evidence – when the recordings, videos, and photos exist at all – is a paradox. You can’t prove “erasure” without material evidence of what was erased. I always think about the bands that didn’t have access to recording at all. Like the Zen koan about the tree falling in the forest - did their instruments ever make a sound?

Fortunately for the Phantoms, the label Pressed for Time released their 7-inch– their only official physical release, “Any Day / Alien” the one I found on YouTube. The people running the label were friends of the band and put up about 3,000 dollars to produce 2,000 copies.

Luckily, the Wayback Machine archived the band website Micky created, and Skreeg safeguarded much of their ephemera, including audio and photos. The band pays him thanks on their site, writing, “He has spent countless hours diligently digitizing and encoding the songs from a pile of gnarly tapes we had salvaged from our soggy basement. We have to give him MEGA credit for sifting through hundreds of hours of cassette tapes.”

“I was into taping anything because I just really value being able to archive and hoard music performances and I was lucky to know a bunch of musicians and live with and starve with them,” Skreeg said.

Micky’s involvement in the music scene reached a turning point around 1993. “I was tired of being in a room full of drunks every night,” she said. Another reason is that she wanted to be creative and her all-girl band, She’s So Loud, only wanted to play covers. Micky formed the shortlived punk metal band Diabolix. “After that, I felt I could be of more help to musicians by honing my web development skills,” she said.

Micky Metts in the Boston Globe alongside other rule-breaking women, November 6th, 1980. Photo courtesy of Micky Metts.

As a writer and in my role as an archivist of women in early punk, I am doing what I can to un-erase the story of the Phantoms and their guitarist and singer Micky Metts. I included a biography of the band in Hit Girls, and I couldn’t tell you how many outlets I’ve contacted to run a feature of or one of my interviews with Micky. Other than Please Kill Me (a punk site that folded a week before my article’s deadline), I have not had another outlet jump on my pitch.

I had looked forward to the article being published on PKM. The feature I wrote for the site on a once-hidden grunge artist named Tina Bell picked up steam in part because of the publication’s audience. It was shared thousands of times by people excited to read her story wanting to know more. I implore readers of this article and punk enthusiasts to share this feature widely, as well. This is my second-ever article on Substack in the year that has gone by since I made an account (and I think my mom is my only subscriber).

I hope a record label reaches out to re-release Wagon Loopy on vinyl (and provide the Phantoms with a fair contract). I hope an editor who cares about the preservation of art and culture reaches out to publish one of my many interviews with her. I will respond.